Labor Under the Kremlin Regime

(10 August 1946){{}}

From The Militant, Vol. X No. 32, 10 August 1946, p. 3.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

On the eve of the war the question of “mobilizing” manpower became increasingly one of the burning problems of Stalinist economic policy. The constant expansion of the armed forces, the successive mass drafts following the outbreak of hostilities, depleted the factories and the collective farms of the bulk of adult manpower.

The “labor market” was in a permanent state of crisis. Women, children, the aged, the invalids, were drawn in successive waves into production in order to maintain, for better or for worse, the volume of industrial output. This was possible only through gravely lowering the productivity of labor while increasing the absolute number of those employed in industry and agriculture.

_

Conditions Worsen

When the bureaucracy ran up against limits to which it could exploit each individual physically, and the demographic limit of exploiting the Soviet population as a whole, the growing void, resulting from constant losses at the front, and from the growing needs of the expanding heavy industry, could be filled only by forced deportations, first the Mongols, next the Poles, and finally, prisoners of war and German workers.

This trend has now been climaxed by a systematic campaign in the Balkan countries to stimulate peasant immigration to Russia.

But the constant crisis of the Soviet “labor market” is not occurring in conditions of industrialization or expanding production, expanding mass consumption. These are the general conditions which automatically produce a social transformation, namely, an influx of peasant families into cities, and the resulting process of proletarianization which is accompanied by mechanization of agriculture.

On the contrary, this crisis occurs at a time when mass consumption in the cities is held down to almost unbearable levels – that is to say, when the general shift is a flight to the countryside, which in its turn feels an acute need of manpower as a result of de-mechanization.

Unable to appeal to the masses’ understanding, energy and revolutionary spirit of sacrifice, the bureaucracy had no means of maintaining and increasing the number of industrial workers other than – coercion. Just before the war there came an uninterrupted series of measures designed to forestall any possibility of “indiscipline” by the workers.

Since 1940 no worker could quit his factory without the authorization of the management. This authorization could be granted only in case of illness. The June 26, 1940 decree made unauthorized departure from the factory punishable by two months’ imprisonment. At the same time, this decree made all “labor delinquencies” felonies, under the jurisdiction of a single judge, outside of the province of normally functioning courts, and subject to prosecution within five days of the commission of the “delinquency.”

A July 17, 1940 decree and another of July 24 set severe penalties for directors who failed to press charges against “delinquents” and judges who proved too “indulgent.” Other and even harsher decrees followed.

In the fall of 1940, the Soviet press published a flood of letters from women of the privileged layers, demanding that these decrees also be extended to servants. Nothing can better characterize the monstrous degeneracy of Soviet society – a society calling itself “socialist” – than demands of privileged female parasites that domestic slaves be “punished” for coming late, leaving their jobs, etc.

The decrees of July 12 and 27, 1940 increased the legal workday. At the same time the number of legal holidays and halfdays was cut to less than half. The way in which the bureaucracy “fought” an inflation resulting from the mounting quantity of currency in face of the scarcity of consumers’ goods was : reducing hourly wages in order to keep the nominal wage at the same level, despite longer hours ; introducing night work, and so on. Finally, we know that since October 1940 compulsory labor has been introduced for all youngsters between the ages of 14 to 17.

When the war finally ended, the manpower situation in the USSR was lamentable. An American journalist, whose tour covered thousands of collective farms, did not find more than five per cent of male labor. It is estimated that nine million industrial and tractor station workers were killed or deported during the war.

_

Post-War Changes

However, while the manpower crisis remains as acute as during the war, the conditions under which it now manifests itself have drastically changed. With consumption slowly returning to normal levels, the different industries show a tendency to “compete” for labor, by granting bonuses and special advantages. The resistance of the workers increases.

Contact with superior conditions in the Soviet occupation zone, where in some instances the workers have their own freely-elected factory committees, their own “wall” newspapers containing free criticism, where the police terror is not comparable to that which reigns in Russia – all this increases the will of Soviet proletarians to fight for better living conditions. As a result of their pressure, a number of laws passed in 1940 have been abolished. For example, there has been abrogated a, particularly odious decree which made obligatory work books, where a record was kept of all “disciplinary penalties” (tardiness, etc.). An accumulation of these penalties incurred an automatic withdrawal of ration cards and lodging permits.

A tragic incident recently reported in the Swiss press shows both the still prevailing and terrible penury of workers and the growing pressure of the masses, which forces the government to grant unparalleled “concessions.”

As a matter of fact, for the first time in 20 years, the administration of a Ministry was openly discussed in the columns of Pravda, and meetings of workers, housewives and trade unionists were held in order to collectively debate the possibility of improving the situation through popular initiative. Involved was the Ministry in charge of manufacturing artificial limbs for Red Army veterans. These amputees number millions, and industry needs them urgently. Yet, the production figures of artificial limbs remains more than 50 percent below the plan, and their quality is so poor that they soon render the amputee incapable of performing any work whatever. It is characteristic that this discussion seemed to proceed with real freedom ; that it was provoked by discontent made public by Pravda, and that it concluded in neither the removal nor the imprisonment of the Minister in question.

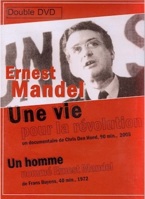

Ernest Germain{{}}